Greatly disturbed by the suffering he saw in the world, 29-year-old Prince Gautama Siddhartha (563-483 BC), who was later called the Buddha (enlightened one), left his wife and young child and set out on a search for the meaning of life.

What he observed was the impermanence of the world—nothing lasted. In spite of this, people desired these impermanent things. They desired to hold on to life, health, possessions, and each other. But life, health, possessions and people pass away. Human desires would always ultimately disappoint. This, he reasoned, was the cause of human suffering.

Therefore, he concluded that if he could kill desire, if he could be tranquilly unaffected by either good or evil, his suffering would cease and he would be happy. He would be free from pain and the endless cycle of reincarnation. This was Nirvana.

It is ironic, though, that driving the Buddha’s rigorous pursuit to kill his desires was one great human desire: lasting happiness.

There was also a huge, vacuous hole in the Buddha’s pursuit of lasting happiness: no God. The Buddha didn’t say much about God’s existence because, frankly, to him God was irrelevant to human happiness. Rather, happiness was being free from desire-induced suffering and reincarnation. Happiness was the blissful end of individual existence—a sort of sweet annihilation.

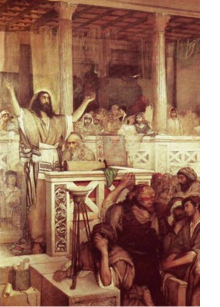

How different are Jesus’ answers from the Buddha’s. When a rich and troubled young man, not so different from the rich and troubled young Gautama, sought out Jesus’ direction for eternal happiness, Jesus replied,

How different are Jesus’ answers from the Buddha’s. When a rich and troubled young man, not so different from the rich and troubled young Gautama, sought out Jesus’ direction for eternal happiness, Jesus replied,You lack one thing: go, sell all that you have and give to the poor, and you will have treasure in heaven; and come, follow me. (Mark 10:21)

Notice that Jesus did instruct the man to become detached from his possessions. But he did not mean a Buddhist detachment. He said it another way here:

The kingdom of heaven is like treasure hidden in a field, which a man found and covered up. Then in his joy he goes and sells all that he has and buys that field. (Matthew 13:45)

The message is clear: desire the treasure! Desire it enough to count everything else as loss in order to gain it (Philippians 3:8).

The difference is that the Buddha wants to be desire-less and completely absorbed into the impersonal cosmos. Jesus wants us to deeply desire and be completely enthralled with the Person in whom we live and move and have our being (Acts 17:28).

That’s why, in the battle against sinful desires, Jesus is so much more helpful than the Buddha. He knows that our desire for happiness is designed by God, and so is our desire for permanence. They are not evil. Here is what is evil:

Be appalled, O heavens, at this; be shocked, be utterly desolate, declares the Lord, for my people have committed two evils: they have forsaken me, the fountain of living waters, and hewed out cisterns for themselves, broken cisterns that can hold no water. (Jeremiah 2:12-13)

We are designed to be satisfied with the one eternal (permanent) God. Evil is when we believe that God will not satisfy us and therefore pursue happiness in something else. That’s the essence of sin. And the way we fight sin is not to kill desire, but to abandon our futile desires for broken cisterns. There is no water there. Go to the Fountain!

Jesus and the Buddha agreed that pursuing ultimate happiness in transient things is futile. But they direct us to opposite solutions. The Buddha says satisfaction is treasuring no thing. Jesus says it is treasuring God. In God we get all things. In no thing we get, well, nothing.

By John Bloom